South Korea’s Democracy Tested as President Yoon Declares Martial Law

South Korea’s President Yoon Suk-yeol declared martial law in an unprecedented move on Tuesday night, marking the first such proclamation in the nation’s democratic history since 1979.

His decision, announced on national television at 11:00 pm local time (14:00 GMT), was ostensibly aimed at countering national security threats from North Korea.

BBC News report indicates that political analysts contend the declaration was a desperate manoeuvre to counter mounting political setbacks and opposition pressure.

President Yoon’s address accused “anti-state forces” of destabilising the country and justified martial law as necessary to “crush” them.

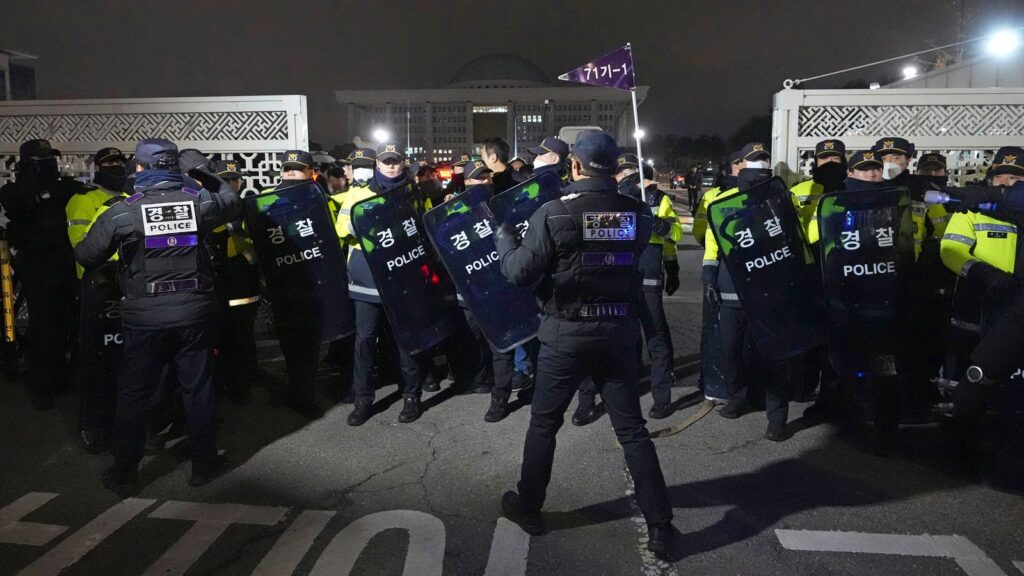

The announcement triggered an immediate deployment of military personnel and police across the capital.

Helicopters landed on the National Assembly’s roof, troops fortified the parliament building, and the military issued a directive banning political gatherings and placing media under its control.

However, the backlash was swift and overwhelming. Opposition leaders denounced the measure as unconstitutional, and even members of Yoon’s conservative People’s Power Party criticised the president’s actions.

Main opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, head of the Democratic Party, called for lawmakers to convene at the National Assembly to reject the measure.

He also rallied ordinary citizens, warning: “Tanks, armoured personnel carriers, and soldiers with guns and knives will rule the country… My fellow citizens, please come to the National Assembly.”

Hundreds of citizens responded, gathering outside the heavily guarded parliament. Protesters chanted, “No martial law! No martial law!” Local media captured tense but mostly peaceful confrontations between protesters and police.

Inside the parliament, legislators worked swiftly. By 1:00 am on Wednesday, a majority of lawmakers – 190 out of 300 – voted to annul Yoon’s declaration, deeming it invalid.

Under South Korean law, martial law cannot persist if the parliament rejects it.

President Yoon’s dramatic decision has sent shockwaves through South Korea, a nation that has prided itself on its democratic progress since transitioning from military rule in 1987.

Critics argue that the president’s invocation of martial law was less about national security and more about quelling political dissent.

Since the opposition’s landslide victory in the April general elections, Yoon’s government has struggled to pass legislation, while his administration has been dogged by corruption allegations.

Recent controversies include an expensive gift allegedly accepted by the First Lady and accusations of stock manipulation.

The opposition has ramped up pressure, proposing budget cuts and impeachment measures targeting key officials.

Despite Yoon’s claims linking opposition parties to North Korea, no evidence has been presented to support these allegations. His declaration of martial law is being described as a miscalculated attempt to consolidate power amid dwindling public support.

For now, South Korea’s democratic institutions appear to have held firm against the unprecedented challenge.

However, the situation has left the nation on edge. Protesters outside the parliament called for Yoon’s resignation, chanting, “Arrest Yoon Suk Yeol.”

A Speaker of Parliament remarked in a statement: “We will protect democracy together with the people.”

The coming days will determine whether President Yoon can navigate the fallout from this political and constitutional crisis, or if his actions will lead to further instability in one of Asia’s most robust democracies.